Project

Understanding poverty

We do the poverty snapshot to understand how people experience poverty and what policy makers can do to help. Last year’s report focused on the effects of COVID-19 and the Black Lives Matter movement. This year, the gap in information in a changing context was something we grappled with. The five-year census will be released in February 2022, and the Income Survey data — where our poverty rates come from — is always two years behind. But in 2021, we wanted to know more, so we looked to additional sources to give us a clearer picture of where we are, where we’re headed, and how we can help build a just recovery.

From that research, we learned that affordable housing waitlists are long and housing is getting more expensive. We learned that food bank use is at an all time high and food prices are rising at the highest rate in nearly 20 years. We also learned that a lot of people are receiving effective government supports and coming out of poverty. So, who is falling through the cracks, what solutions will prevent or seal the cracks, and how can we better address the root causes of poverty?

Overview

Income poverty has decreased overall in Canada, Alberta, and Calgary, as well as in all other provinces. However, one in ten Calgarians are living below the poverty line.

Child poverty has decreased in Alberta and Canada over the last five years. The Canada Child Benefit and Alberta Child and Family Benefit are credited with the decrease, though provincial subsidy rates and conditions have fluctuated over the last few years, as outlined in Vibrant Communities Calgary’s Response to the Alberta Budget 2021. Both programs have criteria that might make some families ineligible, like having completed tax returns.

Poverty is over-represented among single people, who experience the greatest depth of poverty. On average, those experiencing poverty are well below the poverty line: 55% of the poverty line in 2018 in Calgary, and 51% in Alberta in 2019.

The rate of poverty among single people remains stable in Canada and Alberta. While income supports for children and families have been effective, those for single people remain insufficient. For example, Income Supports for a single person considered employable in Alberta was set at 38% of the poverty line in 2019.

Incomes for people with disabilities collecting Assured Income for the Severely Handicapped (AISH) reach 85% of the poverty line. Indexation — changing the amount to keep up with inflation — was paused in 2019. AISH is the most generous program for people with severe long-term disabilities in Canada, but it is difficult to qualify for. Income supports in Calgary for a single person, with barriers to full-time employment, were the lowest in Canada in 2019, at 44% of the poverty line: $13,680 less than what they need to meet their basic needs.

Data from the 2016 census shows poverty is overrepresented among racialized people, who experience a 14% poverty rate, recent immigrants (20%) and Indigenous people (27%). Indigenous and Black Calgarians are more likely to experience deep poverty, which means making less than 50% of the poverty line.

While women remain over-represented nationally among those experiencing poverty, this trend appears to be diminishing in Alberta and Calgary. Equity issues persist, however, with women making up a greater share of people on low wages. They are paid less than men with the same qualifications. Family incomes are lowest for lone mothers, and women are over-represented in core housing need. Lone mothers and senior women are the least likely groups to own a home, which for most Canadians is their most valuable asset. Women are more likely to take on care-giving responsibilities for children and elderly family members, which adds to their responsibilities, and their expenses.

Unemployment in Calgary remains higher than before the pandemic, averaging more than 10% for the first nine months of 2021. National and provincial trends show youth, racialized communities, and those who worked low-wage jobs, have experienced unemployment more, and for longer periods of time. Long-term work interruptions from COVID-19 restrictions have also affected financially-vulnerable families and low-wage workers more. These impacts can be felt for years — 1 in 5 people unemployed long-term see more than a 25% loss in income even five years later.

The price of food has risen nearly 4% and the average Calgary family is spending almost $70 more for groceries every month. Food is expected to get even more expensive. Additionally, visits to the Calgary Food Bank have gone up by 44% since 2019.

While there is evidence that COVID-19 emergency income supports had a positive impact on mental health in Calgary, mental health in Calgary and Canada has suffered since 2019. This is reflected through surveys on self-reported health, increases in calls to police and crisis centres, and, substantial increases in drug poisonings, and tragically, related deaths.

Some people were hit harder by the pandemic — financially, physically and mentally — particularly those already over-represented in poverty. Understanding the Impact of COVID-19 showed many Calgarians did not qualify for emergency supports or experienced barriers to receiving them, despite being disproportionately affected by the pandemic.

Currently 81,240 households are in need of affordable housing in Calgary. These are households that spend more than 30% of their income on shelter and earn less than $63,267 annually. In 2018, 4,200 households were on a waitlist for subsidized affordable housing in Calgary. As of 2020, the City of Calgary estimates 15,000 more units of affordable housing are required to meet the need and Calgary ranks with Toronto, Hamilton, and Kitchener for least housing supply.

Up 44%

Food Bank use from 2019

$70

Monthly extra money required for an average family's food

80,000+

Households in need of afforadable housing

Building a just recovery

The last two years have been difficult with challenges that affected everyone but especially the most vulnerable. It is too soon to tell what this will mean long term, but we know that mental health and relationships have suffered and that many people are struggling to meet basic needs. The 2021 Poverty Snapshot revealed some answers, but also plenty of questions. Are we measuring poverty accurately? Who is falling through the cracks? How do we make sure benefits don’t keep people in poverty? We don’t know enough about people experiencing the deepest level of poverty, and though poverty seems to be decreasing, affordable housing waitlists are getting longer, and food bank use is increasing. Poverty is costly to health, future generations, and the very fabric of our communities. To address it effectively, we need a clear picture of poverty in our city, political will to make necessary changes, and heightened recognition that poverty initiatives benefit everyone.

Recommendations

Provide income supports that reduce poverty

Allocate sufficient funds in the 2022 Provincial budget for the Stronger Foundations Affordable Housing Strategy

Accelerate existing provincial targets for affordable housing

Reduce over-representation of Indigenous people with core housing needs

Prioritize neighbourhood investments and zoning changes based on an equity framework at the City of Calgary, to support affordable lifestyles

Want to learn more?

Download the full report to learn more about the data, dive deeper into topics, our references, and more.

Focus Areas

Tags

Attribution

Related Projects

Alberta's Gig Economy

Calgary Social Policy Collaborative’s new report exposes the pressures facing Alberta’s gig workers and the policy tools that could better support them

Calgary’s Living Wage is $26.50 per hour

Alberta’s largest city sees a $2.00/hr jump in living wage compared to 2024

Making Ends Meet

Stories of lived experience told through community voices

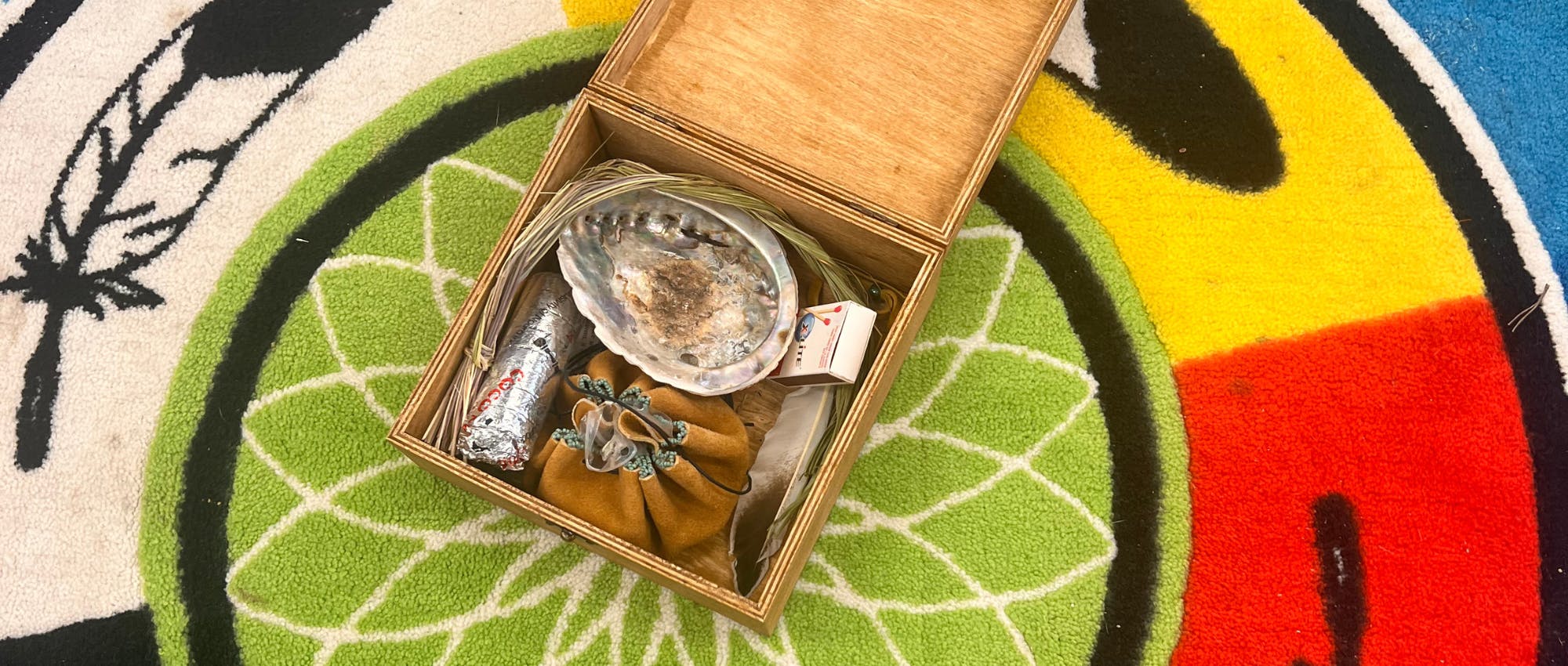

Indigenous perspectives on building a future where there is enough for all

Indigenous teachings and oral storytelling traditions capture the conversations, wisdom, and experiences shared during the pipe ceremony